“Look at that beautiful sky,” said a friend to Johan Hendrik Weissenbruch. “Oh well, I paint it better” was the answer.

A world without clouds would be an outright nightmare for wildlife photographers. “A clear blue sky may be ideal for sun worshipers and patio owners, but as a landscape photographer you really want to see some clouds in the picture,” said Karin Broeckhuijsen, nature photographer from Drenthe. Landscape painters from the 19th century would have completely agreed with her, with the difference that they captured the ever-changing cloud play in nature with a brush and not with the camera and that the words “sun worshiper” and “terrace manager” did not yet exist.

Landscape painters from the 19th century would have completely agreed with her, with the difference that they captured the ever-changing cloud play in nature with a brush and not with the camera and that the words “sun worshiper” and “terrace manager” did not yet exist. For many romantic artists, the sky was the most important part of landscape painting, and in the early 19th century this brought about a complete cloud mania among Northern European artists. The different cloud formations, which always showed different shapes, atmosphere and light, fit perfectly in the atmosphere of romanticism, where drama and glorification of nature played a major role.

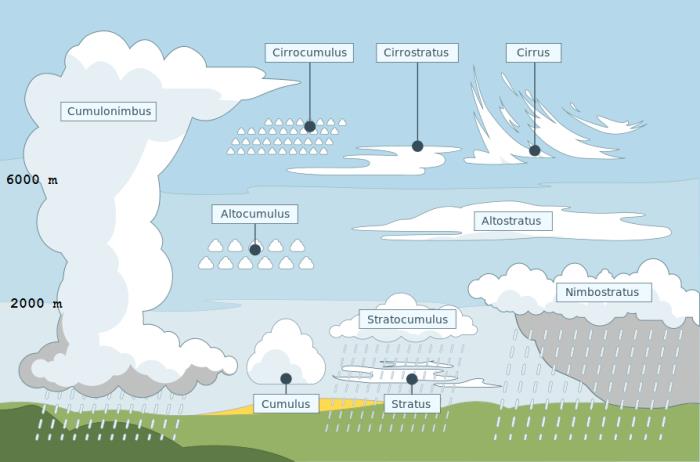

To map all clouds, British amateur meteorologist Luke Howard published a cloud rating system in 1802. His arrangement, with Latin names and a classification by height, size and shape, is still used by meteorologists today, but has expanded over time. The system has four cloud families, the high clouds (6-12 km), the medium clouds (2-6 km), the low clouds (under 2 km), and the vertically developing clouds, through all layers. These cloud families are further subdivided into cloud types, depending on the height at which they are located. Sweeping clouds (cirrus), cumulus or cauliflower clouds (cumulus), layered clouds (stratus) and the vertically developed clouds (nimbus) moving vertically through all layers.

Cloud map, source Meteo Julianadorp

Cloud families: high clouds – middle high clouds, low clouds – vertically developing clouds

Clouds as ‘our painters’ saw and painted them: Cirrus – Cirrocumulus – Cirrostratus – Altocumulus – Altostratus – Stratocumulus – Stratus – Cumulus – Nimbostratus – Cumulonimbus

Howard’s system became widespread in a short time, and his publication on clouds was a godsend for many romantic painters, who usually sketched in nature. An extensive description about cloud families and cloud genera was a wonderful aid in working out the skies on their paintings in the studio.

Paul Gabriel, En plein air, Teyler’s Museum Haarlem.

The Impressionists seem to be more free to deal with the representation of cloudy skies, although, as with the romantic painters, the basic principle for them is that the sky determines the mood. That freedom was partly determined by their physical presence in the open air; wind and weather were braved to make studies in nature. The story of Paul Gabriel is that he once worked outside for so long that he fell ill and was left with a deafness. Anton Mauve often tried unsuccessfully to persuade his friend Willem Maris to go outside in bad, and therefore ‘interesting’ weather. But Willem preferred to stay at home, by the stove in his studio. His friend meanwhile enjoyed “live” endlessly varied cloud formations and recorded them on the spot.

What were the clouds that the artists could encounter? The most common cloud in the Netherlands is the low-hanging cumulus or “cauliflower cloud”. No wonder it can therefore often be seen on the landscapes of the Impressionists. They are grateful clouds to paint, because of the great light effect they produce. The painter’s hand can often be recognized in the cloud, each of whom gave his or her own interpretation. We are talking about a typical “Maris air”, the recognizable “Weissenbruch cloud” and the thin, gossamer skies of Jan Voerman. The mammatus cloud, literally translated “breast cloud”, is a subspecies of the cumulus cloud cumulonimbus, named after its typical shape. They can be seen just before or after a shower, under low sun, a favorite moment with romantic painters. The “sheep cloud”, or high cirrocumulus, usually indicates an impending disturbance, but the weather is still good for the time being. You often see them in paintings. It meant that the painter could sit outside for a while without getting wet.

In the course of the 20th century, with many figurative modernists, assessing clouds and sky against reality no longer seemed to be a priority. More than ever, clouds convey an atmosphere. The artist takes his freedom: in brushwork, in use of color, in the imagination, including in the representation of his clouds.

John Constable, Study of clouds, The Frick Collection, New York

The question now is what skies will look like, how clouds will react to the warming climate. Our climate is a dynamic system in which not everything stays the same and in which clouds play an important role. Clouds help determine the temperature. On the one hand, they are good reflectors for sunlight – mainly low-hanging clouds contribute to this cooling effect. On the other hand, clouds are also good at retaining heat that would otherwise radiate into space. High clouds are especially responsible for this warming effect. Will the firmament change with more cooling, low-hanging clouds or will it be the high clouds that will change and affect global warming?

In 2018, a group of bachelor students at Delft University of Technology focused on the idea of sowing artificial clouds high up in the atmosphere, as an emergency solution to reflect sunlight and combat global warming. They designed an unmanned aircraft, which is supposed to disperse sulfuric acid in gaseous form at an altitude of nearly 20 kilometers. Their calculations gave the following result. If you want to cool the earth permanently, you will need 350 appliances, each with 35 tons of sulfuric acid on board. They should take off twice a day and bring 5 million tons of sulfuric acid into the stratosphere every year. The group fell silent when they realized what it takes to do climate control in this way and expressed the hope that they would never have to apply it.

Special thanks to Heleen de Boer, DTN Meteo.

This low cloud is the most common in Western Europe and consists of a single cloud layer in which dark and lighter parts almost always occur alternately. Sometimes the elements have fused together and form a closed cloud layer.

Stratocumulus

On the Pelgrom, the tops of the cumulus clouds are “blown” by the strong wind just above the cloud layer. On the Morel II we see a layered spherical stratocumulus. With a bench at the top left of the painting altostratus (medium height cloud). On the Wiegers large, low-hanging clouds stratocumulus in shreds with gray and white pieces. They are massive, sometimes dark clouds that can look threatening. Between these irregular clouds is often a blue sky or even sun rays can be seen. These clouds do not often give rainfall.

This type of low clouds that at the top resemble towers or battlements, we see when the wind direction is chaotic. Usually this is an indication of unstable weather and that a thunderstorm is emerging.

The colors in the sky here are spectacular. The most beautiful colors give the middle cloud. This cloud cover usually hangs high enough in the atmosphere to spread the orange to red color of the sun. The dark spots in the middle cloud turn darker to purple.

Stratocumulus en altocumulus

Clouds developing vertically. Usually they are separate clouds with sharp edges, a dark horizontal bottom and a cauliflower-like appearance upwards. They can come in all shapes and sizes: small, medium and large.

Cumulus

On the Adriaan van ‘t Hoff and Frans Langeveld paintings below, we see large swollen cumulus clouds that appear as thick cauliflowers in an often beautiful icy blue sky (cold air originating in the Arctic region). They can grow into cumulonimbus.

Cumulus congestus

A very strongly grown cumulus cloud. The cumulonimbus, which develops vertically, rises high, often higher than 12 kilometers in summer. In that layer, the air is warmer, so that the rain cloud no longer rises. Above that height, the cloud does not bulge further, but air and cloud spread horizontally. This creates the anvil or mushroom-shaped cloud. The shape of the anvil at the top often foreshadows the arrival of a thunderstorm.

Cumulonimbus

A medium-sized, gray cloud cover that extends over the entire sky and from which there is continuous rainfall. The contours are usually faintly visible.

Thin, patchy high clouds (cirrus) and cirrostratus. A thin type of cloud consisting of ice crystals. It looks like a transparent, translucent blanket with a halo sometimes, through which the sun and moon shine through without problems. Below, more in the foreground, an altostratus frosted glass sky with a few benches of stratocumulus in the back.

Cirrus, cirrostratus, altostratus and stratocumulus